BARNEY McDERMOTT, TOP COP

By CAROL MCCUAIG

published in the Renfrew Mercury 20 May 2008

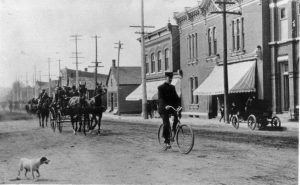

If you enjoy police dramas on television you’ll know that shoot-outs and high speed car chases are often part of the action. Now try to imagine a scene where a lone policeman, armed only with a wooden baton, races to crime scenes on a bicycle land single-handedly captures jail breakers, puts down riots or disarms a gun-toting madman. Improbable, but true.

Over a century ago, Barney McDermott, Renfrew’s police chief, took such occurrences in his stride.

He arrived in town in 1891, when he was 36 years of age. He was six feet two inches tall, with a military bearing. With his black hair, heavy eyebrows and impressive moustache, he was a handsome man.

At that time a local blacksmith doubled as a constable in his spare time, but his main duties, consisted of guarding the town lock-up, sobering up drunkards and chasing cattle off the streets.

Although no job had been advertised, McDermott showed up at a council meeting asking to be appointed as a full-time officer. He was turned down, but he kept coming to meetings until the town fathers gave him the job.

However, they were determined to get their money’s worth. He was required to act as tax collector and school truant officer, and he was on call 24/7, with no relief. Despite the fact that he was a one-man police force, he soon became know as “the Chief”.

In the 1890s Renfrew was no longer the sleepy little village of bygone years. Three railways linked the community with the outside world and several trains stopped here each day. Among the passengers were card sharpers, con men and escaped criminals.

In the beginning it was some time before people understood that Barney meant business. Mischief makers knew that the blacksmith, busy at his trade, couldn’t be in two places at once. They weren’t prepared for a full-time officer who seemed to have eyes in the back of his head. There were numerous complaints about teenagers running the streets at night, robbing hen houses, cursing and swearing, and firing shotguns. McDermott declared an eight o’clock curfew for these lads.

While on patrol one night he found himself surrounded by 15 youths who threatened to beat him up. He coolly proposed a compromise which they accepted; he extended the curfew and they could roam the streets until 8:30!

Renfrew had several hotels which served liquor. McDermott was frequently summoned to deal with drunken men. His method was to take them home in a wheelbarrow, or on a toboggan in winter. If they lived too far away they spent the night in the lock-up, known locally as ‘Barney’s Castle.’ Lock-up wasn’t really the right word; when he first came there was no key to the jail so on more than one occasion he had to sit up all night to guard an inmate.

Reckless driving was a problem. The only way into town was via one of several bridges over the river. He decreed that no horse or buggy might cross a bridge at a speed faster than a walk. He spent his day cycling from one end of town to the other; watching for speeders. The local magistrate was kept busy raking in two-dollar fines, while merchants wrote indignant letters to The Mercury, complaining that nobody would want to shop in Renfrew while this practice was in effect.

Inside town, the speed limit was 10 mph. One day McDermott caught two men indulging in a horse race on the main street. The Mercury editor had a field day when he realized that two members of town council had been hauled up before the magistrate and found guilty. A rival horseman volunteered horseman volunteered to appear in court and testify that their horses couldn’t go faster than 10 mph. The pair preferred to pay the fine.

A job that McDermott had less taste for concerned the jailing of an eight-year-old boy. Called to the scene by a local hotel keeper, he learned that the child had stolen a gold pocket watch from a

patron, who now wished to press charges. There was no mistake about it; the boy had been caught with the watch in his pocket.

McDermott had no choice in the matter. He was forced to take the boy to the local magistrate, who sentenced the small criminal to a month in the county jail at Pembroke. There the child cried so hard for his mother that he was sent home after two days.

The Chief took a sterner line with grown men. In 1893, it was the fashion for wealthy men to wear fur coats. Local stores advertised garments made from astrakhan, raccoon and kangaroo skins. A visitor to the town was seen stealing a fur coat from one of the hotels, but before McDermott could be fetched to deal with him, the thief got away on the north-bound train.

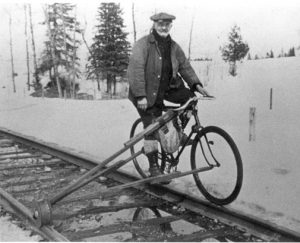

The telegraph operator learned that the man had got off at Chalk River; an hour’s journey from Renfrew and had walked away up the track. McDermott boarded the next train and went in pursuit. As he later testified in court, “On reaching Chalk River I procured a railway velocipede and followed.” A velocipede, used by section maintenance men, was a bicycle which attached to the rail on the track. McDermott pedaled a distance of 19 miles before capturing his fur-clad quarry who was still trudging doggedly up the line.

On another occasion a stake-out paid off. A young man, fined $10 for breaking and entering, skipped town without paying. The magistrate issued a warrant for his arrest and commitment to the county jail, but the burglar boasted that McDermott would never catch him. That was like a red rag to a bull as far as the Chief was concerned.

He tracked the man to his hideout, an abandoned farm on the out-skirts of town where there was an excellent view of the surrounding countryside. From time to time the wanted man could be seen peering out through the windows, but he failed to notice Chief McDermott, who was crouching in the bushes behind the house.

Those were the days when few country homes had indoor plumbing. McDermott knew it was only a matter of time before the burglar had to come out of hiding. As The Mercury later reported, ‘After a time the fellow entered the water closet and there was nabbed by the constable. He was soon studying the interior of the jail.” Another case successfully closed.

In 1897, J.R. Booth’s Arnprior & Parry Sound Railway opened for business. Not everyone was pleased. A farmer near Eganville, whose cattle were upset by the trains, built a fence across a portion of the track which passed by his land. As fast as the section men removed it, he built again. Finally the railway officials sent a special constable to arrest the man but he was afraid to face the farmer alone and asked McDermott to go along. Although it was outside his territory the Chief agreed. They traveled out to the country in state on a special train, called up for the occasion.

Accompanied by the engineer and the baggage man, the officers tramped across the fields to the house, where the farmer meekly agreed to go with them, on condition he could first change out of his work clothes. He went up a ladder into a loft over the kitchen, followed by his wife and daughters.

When half an hour had gone by and nobody had come back down, McDermott went up the ladder and was met by the farmer; brandishing a club. The Chief swung his baton in response. The women picked up some loose boards and began to whack the Chief. The special constable raced up the ladder and held the women back.

Downstairs, the family dog sprang into action. It grabbed the engineer by the pants. The animal was pulled off by the baggage man. Finally the ruckus died down and the small posse, somewhat the worse for wean headed back to the train with their captive. Just another day in the life of a law enforcement officer.

Exactly 100 years ago, a former escapee from Sing Sing prison visited Renfrew. The Chief bet the fellow that he could chain him up in such a way that escape would be impossible. The man accepted the challenge and was placed in a cell with his hands and feet fastened to the iron bars with handcuffs. The cell door was then locked and the key placed in McDermott’s pocket. In exactly two minutes the prisoner was free of the handcuffs, and five minutes later the cell door swung open and he stepped into the corridor, to the applause of the waiting crowd.

Possibly the most dramatic incident in Barney’s career took place towards the end of the 19th century. The gold rush was on in the Klondike, and freight trains passing through town were used by men who wanted a free ride to the West. A young Welshman named Davies, newly out from the old country tried to board a moving train but fell under the wheels, with his foot crushed.

The previous evening, along with a tramp known as Three-Fingered Jack, Davies had arrived by train from Montreal and disembarked at Renfrew, where they planned to hop the westbound train the next day. It was common practice then for tramps to be given over-night shelter in the local jail, and the pair spent the night in Barney’s Castle.

Released in the morning, they spent the day trying to avoid the Chief, whose job it was to guard the station against those trying to hitch a free ride.

When the train came they waited until the last minute. However, Three-Fingered Jack took his time climbing up and the train was gathering speed by the time Davies’s turn came. He lost his grip and fell. The train passed over his leg and he was dragged for some distance before collapsing in the snow.

McDermott took a statement from the victim while waiting for the doctors to arrive. Onlookers were amazed by the young man’s courage. He announced “Well, Chief, I’ve been done up. It’s my own fault! I had the money to pay my way but tried to save it.”

He displayed $143 which had been sewn up inside his clothes. The victim was William Henry Davies, later to become one of Britain’s most famous poets.

In 1909, Barney McDermott himself had the to go West. For a time became a turnkey (jailer) at the Saskatchewan Provincial jail at Regina, and later served as Police Chief at Prince Albert and at North Battlefort.

In Renfrew his name has passed into legend. He is remembered as a feisty man who did his duty as he saw it, even when it made him unpopular. He is buried in the Catholic cemetery just outside Renfrew.